Are You Training Them All?

The Magic 6

As a human, your body moves in pretty much the same way as other humans. In fact, there are six basic movement patterns. Naturally, if you want to be a strong, athletic, healthy human, you train all of these foundational patterns. Here they are:

1. Squat

2. Hinge

3. Lunge

4. Push

5. Pull

6. Carry

But there’s a problem. Not all the exercises that mimic these patterns are right for every body, at least not right away. For example, if you start with the wrong squat variation for your body type, skill level, injury history or goal, you’ll wind up with a banged-up body.

If you plan on training for a lifetime, forget about training specific exercises. Instead, train custom-fit movement pattern variations. You’ll avoid injury, get rid of some aches and pains, AND reach your strength and physique goals. Let’s break it down.

1. The Squat

I bet the image you have in your mind right now is that of a barbell back squat taken to ass-to-grass depth. That is one squat pattern variation, but it’s by no means the only way to squat. And for the record, you’re not less of a man if you don’t squat with the bar on your back.

Think of “squat” as an umbrella term. Under that umbrella, you’ll find the barbell back squat. But the squat movement pattern isn’t about a specific exercise. The pattern is more important than the specific exercise, at least if your goals are performance and longevity.

Does everyone need to barbell back squat? Nope. But do most people need to display and maintain the ability to use synergistic muscular tension, stability and mobility through the torso/hips/knees/ankles from a symmetrical bilateral stance? You bet your ass they do.

The squat pattern is a key player. It’s a movement pattern that transcends its use in the gym. It’s used for routine activities and movement requirements of daily living.

Everyone is different, therefore, everyone must squat differently, especially as it pertains to loading the squat for power, strength, and hypertrophy training. Identifying the proper squat progression is the first step.

Squat Pattern Progressions

Your goal: find the squat variation that’ll give you the most benefits while minimizing risk of injury. How? By assessing your current skill level and trainability.

While there are advanced testing procedures out there, more complex assessment usually isn’t needed. All you need is a simplified progression model to experiment with. Master the first variation, then move up the chain to the next one.

Here’s the basic squat progression used to identify starting points and optimal squat patterns for athletes and lifters. We start with the fundamental movements, then move up to the advanced variations:

1. Bodyweight Squat

2. Goblet Squat

3. Barbell Front Squat

4. Barbell Back Squat

As you can see, the barbell back squat is last on the list. Look around your gym. How many of the people in the squat rack with heavy bars on their backs are using good form? How many look like they’re about to put themselves into traction? Yeah, they need to regress back to the bodyweight squat and get that down first.

And the barbell back squat isn’t even the ideal final squat variation for everyone. Here’s the key: find the “hardest” variation that you can do perfectly. From there you’ll be able to train the squat pattern without internal restriction, get a great training effect, and minimize joint stress. The goal is to move up the list over time and progress strategically.

Once your perfect squat variation is identified, fine tuning setup and execution is the next step. To do that, you find the right squat depth for your body. Refer to this article and take the tests listed: Squat Depth: The Final Answer.

2. The Hinge

The hinge is one of the most important patterns when it comes to protecting your lower back from injury, but many people have lost the ability do it.

The hip hinge is often confused with the deadlift, which is a specific exercise that falls under the hip hinge umbrella. While not every hip hinge is a deadlift, every deadlift is a hip hinge pattern. Many people don’t deadlift because they think it’s too risky. And since the deadlift is the only hip hinge exercise they know, they skip training the entire movement pattern. The result? More low back pain, more injuries.

We must learn to reintroduce and reactivate this pattern. The problem is, most lifters jump right to the barbell deadlift from the floor, or jump right into the kettlebell swing, before mastering the hip hinge.

How many times do you bend over a day? The correct answer is: a lot. That’s why honing this pattern is so important. Master the hip hinge and you’ll avoid chronic flare-ups, lower back tightness, and generalized “neural-lock” of your mobility and flexibility.

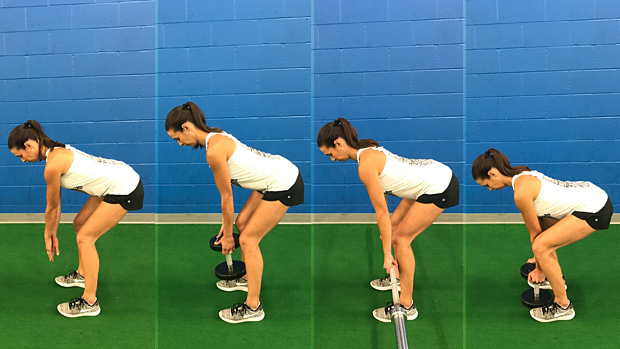

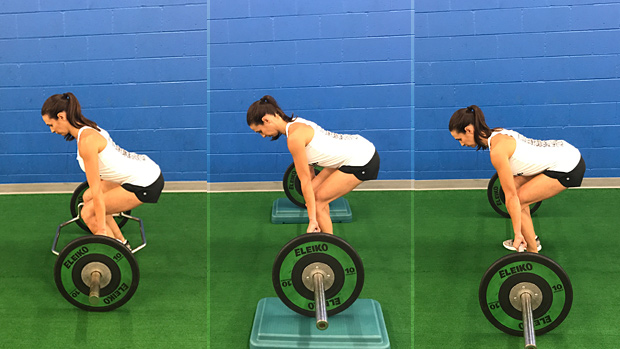

Hinge Pattern Progressions

This pattern needs to be slowly implemented at lower levels to allow motor relearning to take place. Here are the main progressions used to reactivate the hip hinge from the ground up:

1. Bodyweight RDL (Romanian Deadlift)

2. Dumbbell RDL

3. Barbell RDL

4. Dumbbell Deadlift

5. Trap Bar Deadlift

6. Barbell Rack Pull (or lifting from blocks/plates)

7. Barbell Deadlift

Based on their body type, not every lifter will have the ability to pull a barbell off the floor with good neutral spine mechanics. And that’s totally fine. If that’s you, then you’ll just stop somewhere else on the progression list. Remember, based on your God-given body structure, no matter how much you foam roll and stretch, you can never change your bony anatomy. Don’t try to force it.

3. The Lunge

Single-leg function is another overlooked movement pattern. Sadly, many lifters don’t think much of lunge variations. Why? Two main reasons. First, they can’t use as much weight as bilateral exercises. Second, lunges are hard. If you have any weak links or dysfunction, lunges will let you know quickly.

Single-leg training doesn’t mean you’re always doing some balancing act of an exercise more fit for the circus. It can mean that emphasis is placed on one leg/side at a time in an asymmetrical stance. So the “lunge” movement pattern can also be thought of as any unilateral-based movement of the lower body.

Remember that even with single-leg work, it’s impossible to purely isolate one side from another. There will always be an interplay between left and right sides even out of an asymmetrically split stance.

Single-leg exercises unlock strength and movement quality potential. They tap into your “primitive patterning.” You learned to walk in a sequence. You rolled over, crawled, pulled yourself up, and finally learned to stand and walk. Not all of that was unilateral, but the movement between the steps was. And that primitive patterning is what single-leg movements are targeting for re-education.

There are few movements more powerful than single-leg variations for identifying weak links, sticking points, and pain patterns. These exercises can be programmed for strength and size gains, and also developed as a skill to maintain functionality through this protective pattern.

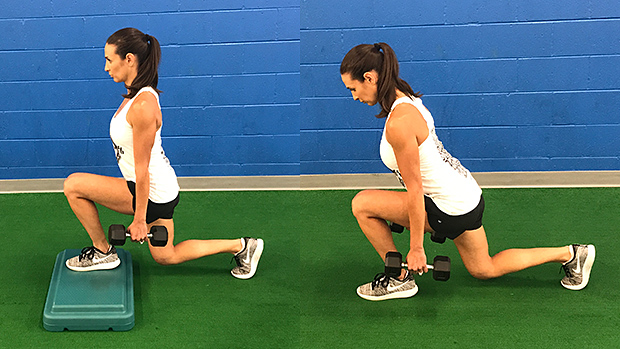

Single-Leg Pattern Progressions

Once a lifter is convinced he needs to add in some lunges, he often jumps right into the forward walking lunge… and ends up disappointed in the results.

That variation isn’t ideal for strength athletes trying to optimize the connection between core and lower extremity stability. It’s actually a more advanced way to lunge that many lifters (especially those new to single-leg training) aren’t ready for. These lifters jumped the gun and moved down the list below too quickly, causing knee pain, cranky SI joints, and angry lower backs.

Take it from the ground up instead, from split stance all the way up to dynamic lunging variations:

1. Split Squat

2. Back Foot Elevated Split Squat

3. Front Foot Elevated Split Squat

4. Reverse Lunge

5. Forward Lunge

6. Single Leg Deadlift

The single-leg lunge pattern does include more hinge-based movements such as the single-leg RDL and deadlift under its umbrella. While there are overlaps between some of the movement patterns, this doesn’t devalue their importance in a good plan built around non-negotiable foundational patterns.

In the lunge pattern, be sure to include BOTH the more knee-dominant variations such as split squats and the more hip-dominant patterns such as RDLs to cover all your bases.

4. The Push

There’s no lack of upper body pushing in today’s gym. From the popularization of the bench press to the polarization of bodyweight push-ups, the push is often overemphasized and under-executed.

We’ve all seen it: newbies jumping straight into the bench press while never first mastering the stability and dynamic action requirements of the more basic pushing pattern – the push-up. Both exercises seem to move through a horizontally-directed range of motion and target the same muscles. But they’re very different when it comes to the static and dynamic stability component of the shoulder complex.

See, movement patterns are classified as either open or closed chain depending on the contact points with the ground. If the hands and feet are in contact with a stable surface like the ground, the movement is a closed kinematic chain. If the hands or feet are freely moving through space, that’s an open kinematic chain.

With the push-up, the hands are anchored to the ground (or stable surface) that alter the way the spine, gleno-humeral joint, scapula and acute muscular stabilizers of the region articulate. In this closed chain, the shoulder blades are able to move freely against the thoracic cage placing more of a dynamic stability emphasis on the musculature controlling this position.

This skill of stability, tension, and torque output in the shoulders and upper back is something that must be mastered in order to translate into a more static stability-based position such as the bench press.

Starting with the mastery of the push-up progression allows the biggest bang for your buck in full-body motor learning through the push pattern. From integrated core and hip stability to upper back and shoulder tensional recruitment, the push-up is a key player in learning how to generate stability in order to display power and strength. Once this skill is honed in at the horizontal plane of motion, vertical pushing will be the next challenge.

Upper-Body Pushing Pattern Progressions

Since upper body movement is led by the shoulder, the most mobile ball-and-socket joint in the body, there’s a need to break down both the push and pull movement patterns into vertical and horizontal planes of motion.

Pushing development starts in the closed kinematic chain and horizontal plane of motion with the push-up, and is progressed up through the barbell bench press. Though the barbell bench is the final pattern, mastery of the push-up will allow a lifter to move into the vertical pushing patterns while continuing to progress through the horizontal patterns as well.

Below are the movement progressions for both the horizontal and vertical push patterns that can be used to identify an ideal movement pattern variation for a lifter based on skill level:

Horizontal Pushing

1. Hands Elevated Push-Up

2. Push-Up

3. Dumbbell Bench Press

4. Barbell Bench Press

Vertical Pushing

1. Single-Arm Dumbbell Overhead Press

2. Dumbbell Overhead Press

3. Barbell Overhead Press

The success of a perfect push is highly dependent on the stability of the pillar unit consisting of the hips, core, and shoulder working together. It would be shortsighted not to have a deeper look into more isolated core and hip functional stability, and that’s what we’ll be looking at in the carry.

When progressing through the horizontal and vertical pulls, be aware of not only the function and patterning of the shoulder and upper body, but of the entire body, especially the core and hips and their ability to display and maintain good positioning, tension, and control throughout the dynamic motions at the shoulders.

5. The Pull

The upper-body pull pattern may be the most misunderstood pattern of the upper body, especially as it pertains to developing bulletproof shoulders and a resilient back.

We know that strong and stable shoulders depend on pulling more than pushing, but where many athletes miss the boat is not differentiating between types of pulling and the planes of motion that each pull takes place in.

The most popular “pull” takes place in the vertical plane of motion: the pull-up. From CrossFit kips to military PT testing, the pull-up has been ingrained in our physical mentality for decades. But it’s important to remember that not all pulling variations were created equally.

The vertical pull more closely resembles a push-based motion – it places the shoulder into internal rotation during the dynamic action of movement itself. This can be a problem, especially when chronic internally-rotated daily positions and internally-rotated training compound to create a shit storm of front-sided shoulder pain.

While there’s nothing wrong with internally-rotated movements at the shoulders, they must be monitored closely to avoid chronic overuse and dysfunction through the front side of the gleno-humeral joint and the shoulder complex in general. Because of the popularization of box-based facilities, the majority of pulling is centered around the deadlift and the pull-up, which are both internally-rotated movement patterns at the shoulders.

In order to create full-body stability at the shoulders through the pull, the horizontal pull (the row) must first be mastered before introducing the more complex vertical pull variations off the pull-up bar and beyond.

The back and upper shoulders were designed to function as primary stabilizers of dynamic actions that usually take place in pushing movements. This means that these patterns can be trained hard, and under high relative intensities, while literally being trained daily. Mastering the pull from a stable core and posterior hip unit will help develop the strong backside that can support both athletic and functional endeavors alike, and that’s exactly why this pattern must be a priority.

Upper Body Pulling Pattern Progressions

The pattern must first be introduced and perfected from a full-body stability based position, which is achieved in the inverted row. From this position, the pillar is challenged to generate tension and create isometric stability through the legs, hips, pelvis and spine, while the upper body works to generate dynamic force in the pulling plane. You’re only as strong as what you can actively stabilize. That’s why prioritizing this pattern yields big results.

Below is the functional progression of movement patterns in the horizontal pulling plane. This progression is based off of postural and static requirements of the pillar during the active rowing motion. From having the spine totally stabilized in the chest supported row, all the way up to needing to actively stabilize the hip hinge pattern through the pillar during the bent over row, it’s clear that the majority of weak links are identified in the core, as opposed to the shoulders in the pulling plane.

Horizontal Pulling

1. Chest Supported Row

2. Inverted Row

3. Single Arm Dumbbell Row

4. Barbell Bent Over Row

The vertical pull pattern needs to be de-emphasized in training sessions, and re-emphasized in evaluation of pillar function into the overhead position. While earning the right to get back up on the pull-up bar, don’t hesitate to use the vertical pull to evaluate overhead positions at the gleno-humeral joint, rhythm of the scapula, or stability at the core and pelvis.

Vertical Pulling

1. Lat Pulldown

2. Assisted Pull-Up

3. Pull-Up

Once you’ve mastered the vertical and horizontal pulling patterns, strategic programming around these two planes of motion needs to be addressed. A majority of lifters will do well with a 2:1 ratio between horizontal to vertical pulling. Keep this in mind in terms of total reps completed over a weekly workload.

6. The Carry

Moving your body through space with smooth stability and control has become a lost art. While the carry pattern can absolutely include loaded variations like the farmer’s walk, this pattern is more broadly associated with generalized locomotion of the body. From walking to running, sprinting to reactionary agility, an athlete must display the ability to control his body through space and under a multitude of challenges.

There’s something simple, yet truly powerful about the gait pattern that needs to be tapped into in order to truly maximize performance while maintaining movement abilities over time in a protective way. Due to the reciprocation of the lower and upper extremities during walking and running, the core is targeted to function as it was originally designed to function, and that is the transference of forces in and out of the extremities.

This region must be challenged in terms of proximal stability with distal mobility and load when looking to progress athletic performance or getting out of pain. This is why walking in addition to sprint work, loaded carries, and sled pushes/drags are foundational movements in smart programs.

But in order to reap the most benefits while minimizing risk of injuries, there must be a proper progression. We can’t start out with sprints and max effort loaded carries. We first must learn to walk before we can run.

Carry and Locomotion Pattern Progressions

Here’s the golden rule about carries: If you’re going to train the carry movement pattern, you must assess, coach and perfect the basic walking pattern first. Never load dysfunction, even if it’s walking. From walking on up, here’s the loaded progression of carries.

1. Walking

2. Farmer’s Carry

3. Unilateral Farmer’s Carry

4. Front Loaded Carry

5. Mixed Grip Carry

6. Overhead Carry

Carry patterning is primarily programmed as “core emphasized” training in many programs. Along with basic carries, open your mind to specific combinations of hand positions, tempos of walks, and duration of time under tension, just as you could any other loaded movement.